Ghost Track, Cayuga Motor Speedway

In Search of Canada’s Finest Oval

Bobby Markos writer / Jul 19, 2015

When I arrived in Hagersville, Ontario, I started to feel a bit relieved. It was a major landmark on my scribbled directions, and reaching there meant that I had only a bit more of a stretch to go. I had resorted to using a handwritten map in the first place because the “golden age of technology” had shot me in the foot. Roaming cell phone charges per minute in Canada ranked slightly more expensive than a gallon of petro, and my GPS was informing me that there were indeed a couple of different “901 Haldimand 20” locations. That left me no alternative but to confine myself within the walls of my car and hope that my handwriting was legible enough. In theory, my destination should prove easy enough to find. I mean, Cayuga Motor Speedway was arguably the largest and most famous racing facility in the Great White North. But, seeing as how it was located “way out in the middle of no man’s land” as my father used to put it, I didn’t want to chance getting lost and missing my only opportunity for a visit; after all I had just an hour window before I needed to head onto Buffalo.

As I continued south on Route 20, the thought of my father and his dad before him out on these same roads so many years ago, armed with a road atlas and a copy of the Speedway Directory made me smile. Here I am living in a time when a satellite can zoom in on the top of my head and I’m feeling completely astray. A sense of panic began to rise as the miles on my odometer continued to click off and yet I had found no racing Mecca. But sure enough as that cold sweat began to collect at my temple and my knuckles began to turn white, I spotted a clearing off to the left. As I got closer, this great estate of Canadian racing history poured out like water from a glass. Its welcoming sign, still armed with 2009’s race dates, sat loyally like an old knight protecting his aging queen.

Cayuga was truly that, and as I first laid eyes on this crown jewel of Canada, I could see that she was resting heavily under Earth’s reemerging might. I tiptoed my vehicle onto the property, as if subconsciously trying to avoid disturbing the history of its hallowed grounds. Bringing my car to a rest near the ticket booth, I got out and took in the scene that sprawled out before me. The first thing I remember was the huge grandstands, looming over the estate like fortress walls, as if they were protecting the racing surface from any outside evil. I ceremoniously gestured to buy a ticket from the lonely shack, which was wearing a skirt of greenery that reached past my knees. As I entered the first section of grandstands, frustration grew as I had yet to see its famous racing surface. Vines had grown up the catch fence creating an almost curtain-like shield. I sought out the best vantage point in the house: the center set of grandstands at the base of the press tower, which sat proudly upon the facility like a crown. I began to climb the weathered wood with my back to the track like an ambitious race fan on a Friday night. Once reaching the top, I turned around and was immediately knocked into my seat. Imagine seeing a great wonder for the first time, the sheer size and brilliance testing your peripheral and causing a sensory overload. I was seriously dumbfounded by its beauty, a track I had heard so much about, and had seen so many pictures and videos of but had never visited.

Its banking hugged two long, dragstrip-like straights in a fashion that made your eyes follow the racing line even when no cars were present. The state-of-the-art infield tower kept the vacant pit road company awaiting the hustle and bustle of crew members like a dog awaiting his owner at home. The pond on the backstretch sat calmly in the summer daylight, but deep within lied the reflections of the countless battles it witnessed over the years. It all felt surreal, surely I was just early and the racing teams hadn’t showed up yet. There was no way that this great complex to sit silent. I sat there for a moment, readjusting my gaze on different points, and I began to notice the signs of aging. Naturally, the greenery was unkempt as grass had grown tall above the retaining walls. The paint on the stands had faded, and the wood sighed beneath my feet. The asphalt racing surface resembled cracked eggshells while the ground beneath began to seep through like yoke. A portion of the press tower sign was sitting beside me, as if someone trashed the place and left it for the next bunch who stumbled upon it. But I know the real culprit here was economy, racing politics, and Mother Nature.

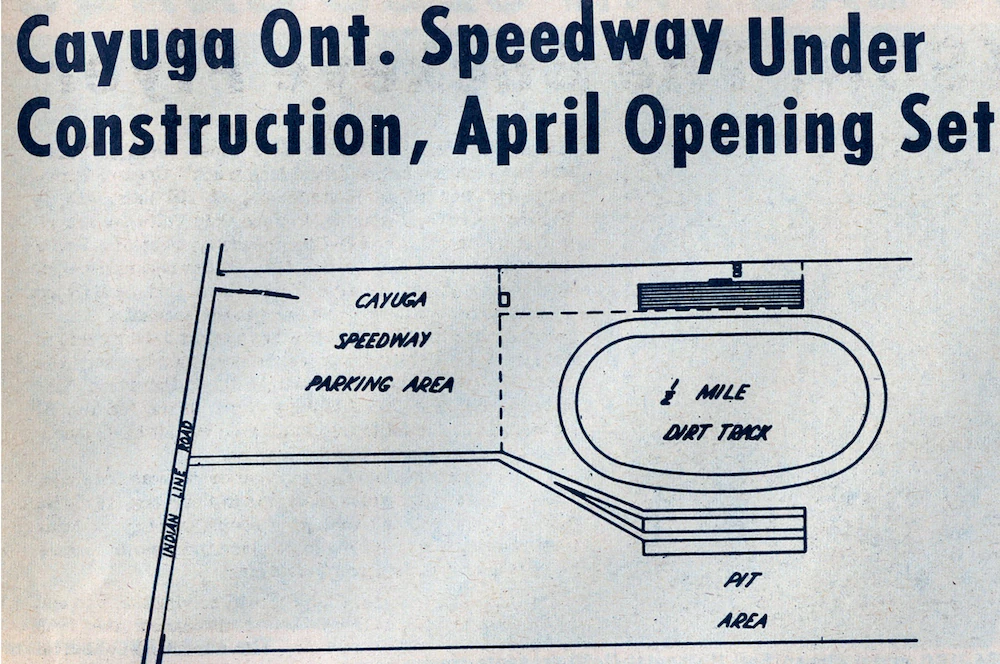

Like Dad had lectured me, it was just a shame that an immense entertainment facility of its kind with such a vast history should have fallen upon the hardest of times. Of course, when the track was first envisioned by original owners Frank Mashell, Wayne Conroy, Milton Chesterman, and Jack Greenhalgh, it was nothing like the dilapidated archive of racing history that sat before me. In fact, in May of 1966 when Cayuga first opened, it was a “D-shaped” dirt oval. The track nestled into the Southern Ontario racing circuit, paired up by weekend warriors with nearby strongholds Speedway Park and Merrittville Speedway. Its Sunday night programs gave Modified sportsman hotshoes like Jeno Belogo an extra shot at a promoter’s bounty. Belogo proved to be a frontrunner in the track’s early history, having racked up multiple wins by late June of its first season. Yet its dirt surface proved difficult to maintain, as a number of its early shows were plagued by dust and rough conditions. Following its debut season Cayuga’s owners appeared fed up with their struggles and sought out a new set of hands to take over. Enter Bob Slack, owner and proprietor of Slack Lumber in Haldimand County, Ontario. Slack was the man behind the curtain of sorts, the largest creditor of the track who had provided the lumber and building supplies for construction of the soon-to-be racing fortress. When the storm broke, Slack, an avid race fan, decided it was time to buy out those involved and take a shot at running the show. His initial promotional attempt encompassed the difficult task of running a program on Cayuga’s extremely stubborn dirt-topped surface.

“Like most people from the outside looking in, he assumed he knew everything it took to prepare a dirt track,” Slack’s grandson Roger, who worked at the track for many years, explained. “After one race he had enough and paved it.” In January of 1968 word began circulating that Cayuga was to be paved. Little did anyone realize at the time that Slack and his 5/8-mile asphalt elliptic would write their way into the history books, becoming Canada’s most celebrated auto racing facility. It would become billed as Ontario’s “International Speedway” and the “Daytona of the North,” and when the Mods took the track later that summer, it was evident that the waters in pavement racing had shifted.

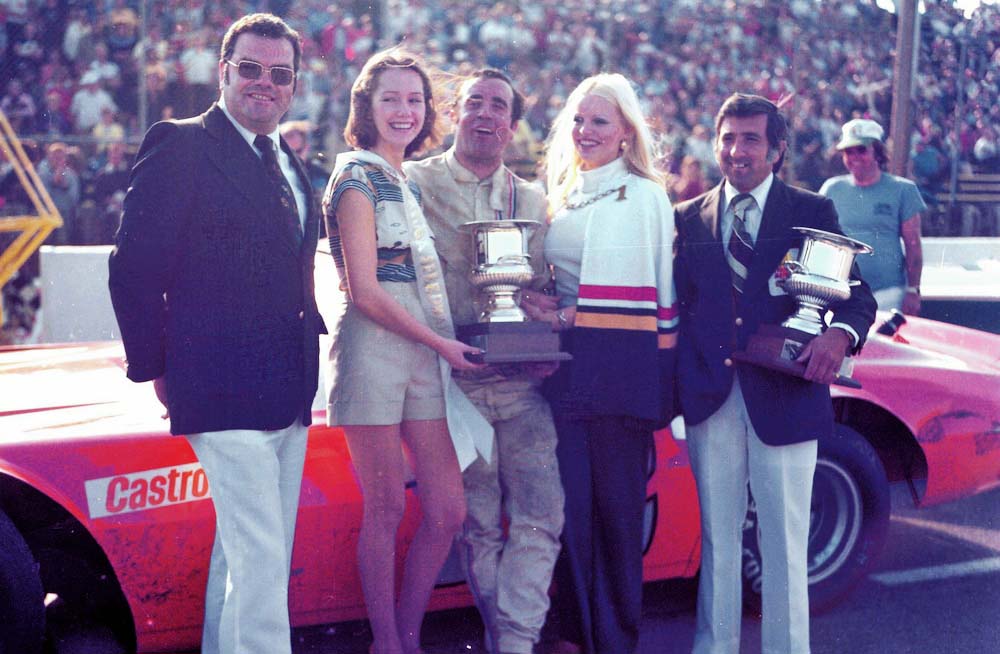

The 1968-69 seasons saw New York Modified invaders Chuck Boos, Billy Rafter, and the Treichler Brothers (Roger and Merv) locking horns on a weekly basis, with Boos taking the inaugural track championship. Late Models shared the bill with names like Paul Putt, Kenny Cassell, and 69 champion Ralph Book, all popular fan favorites. As the ’60s rounded out and Cayuga gained recognition, Slack looked for ways to take things to the next level. And so the ’70s brought about radical change, with late models taking over the headlining slot and Fridays becoming the night of action. This decision proved to be vital to Cayuga’s history, as the early ’70s brought about the track’s first capacity plus crowd at the 1971 Thrush 200, and its first regional points gig, with the birth of the Export A Series in 1972. The radius of talent and prizes grew, and soon legendary short track icons like Jerry Makara, Ed Howe, Bob Senneker, Don Gregory, Ken Reimer, Norm Lelliott, Earl Ross, Don Biederman, and Junior Hanley began gracing Cayuga fans with their presence. The ’70s also saw the debut of the American Speed Association at the track, whose point fund gave American talent like Dick Trickle, Mark Martin, Alan Kulwicki, and Mike Eddy a reason to head North.

“This was before cable TV and before NASCAR was on TV in Canada, so the ASA guys were like rock stars coming to town, that brought all of the Midwest greats,” Slack stated.

A race circuit is only as great as its local rivalry though, and the mid ’70s hatched one of the greatest in racing history: Hanley versus Biederman. Not only did this duo do battle on a weekly basis, but oftentimes the pair would whip up on the talented American contingent when they came to town, as in 1979 when Hanley trumped the ASA corps in the inaugural sanctioned White-Cummins 300.

1980 saw even more change, as Slack decided to forego a weekly program in favor of a specials-only schedule. Cayuga began seeking a wide-variety of racing entertainment, as it popped up on the USAC and NASCAR North Stroh’s tour dockets. Legend has it that the USAC Sprint Car Twin 50s ran in June produced some of the finest oval track action Southern Ontario ever saw. Patrons would also witness appearances from future NASCAR Hall of Famers, such as Bobby Allison, Bill Elliott, and Rusty Wallace with even the great Dale Earnhardt making a visit, pleasing his fair share of guests, when he found victory lane at the 1983 NASCAR North Motion 250.

As the ’90s opened, Cayuga was an established stop on many top-echelon tours, but as short track asphalt racing began a steady decline, the bastion saw its lingering effects. Soon, ownership again changed hands, with former racers Brad Lichty and Garry Evans taking command. The team tried their luck at operations, bringing the International Super Modified Association (ISMA), the Automobile Racing Club of America (ARCA), and the American-Canadian Tour (ACT) through the door.

With the Internet age, the demise of the great oval was well broadcasted. The mid ’00s found the track once again in question, and a new group of investors swooped in with one thing in mind, upgrading the facilities to attract the NASCAR Nationwide (now Xfinity) series. The Nationwide date went to the Circuit Gilles Villeneuve, and Cayuga had to settle for Canadian Tire series, which ran a couple of 200 lappers in 2007 and 2008. Even the national billed act wasn’t enough to rally the troops, and after the July 2009 ISMA show Cayuga shut its doors with the future marked as “unknown.”

I walked across the finish line on the front stretch and I felt this negative energy. It was as if the track didn’t understand what had happened to it, the 300-acre facility sat in an aura of confusion. I felt a thunder in the ground and I looked to Turn 4 to see if Hanley and Trickle were coming, I fully expected to be caught up in their infamous clash. But alas, there was nothing, only painful silence and fading relics of the past. After walking around a bit more I decided to leave, I could bear it no longer: it just wasn’t fair. These sentiments resonated with me for months after my visit. My dreams took me back to Haldimand County, wandering around alone at the once-bustling racing castle, admiring its beauty and observing the undoing roots. So naturally when word came across the wire that the track had been bought by a couple of tobacco producers, Jerry Montour and Kenny Hill, I was overcome with joy. Their stated goal is to reopen in June of 2015. This is exactly what Southern Ontario needs, a couple of businessmen to breathe new life into a resting giant. The potential for Cayuga to once again take its place at the top of the short track hierarchy is there, it just needs some finesse and adaptation, along with some modern day know-how. Yes, there are challenges to overcome, the asphalt short track racing scene is struggling, touring schedules are becoming more regionalized, car counts are shrinking, and race fans are becoming less willing to travel and pay to see programs that don’t feature top-ranked talent.

With enough determination Cayuga could attract huge bills once again, like ARCA, NASCAR, and USAC. Fans and drivers alike will remember how competitive of a layout Cayuga really has. I personally anticipate the day that I can become the third generation of my family to witness battle on the 5/8 mile. I can’t wait to once again sit in those grandstands, only this time with my father and the spirit of my grandfather. I look forward to stories of the battles they witnessed, of Howe, Senneker, and Hanley waging late-model war. Stories that make up the foundation of auto racing, which Cayuga will forever be a part of.

Courtesy of Bobby Markos